This article is written by Dr. Denis Mowbray, and originally appeared as a paper within the Chartered Governance Institute in June 2021. It is re-published here with the author’s permission. It neatly encapsulates NZSA’s core assumptions relating to the role of board members, executives and their combined impact on corporate performance.

Why is it that after nearly three decades of governance reform and development it appears that the same issues, culture, greed and poor-performing boards that drove the original Cadbury report are still evident today? For those who do not remember or possibly were not alive when the Cadbury report was

completed – here is a potted history.

It began with Maxwell Communications, which was a British media business controlled by the notorious Robert Maxwell. A series of risky acquisitions in the mid-1980s led the business into high debts. As a result, the organisation was being financed by diverting resources from the pension funds of Maxwell’s various companies, including the Mirror Group. After Maxwell’s death, while cruising near the Canary Islands in 1990, it emerged that the Mirror Group’s debts vastly outweighed its assets, while £440 million (GBP) was missing from the group’s pension funds.

Despite the suspicion of manipulation of the pension schemes, no action was taken by UK or US regulators against Maxwell Communications. Eventually, in 1992 Maxwell’s companies filed for bankruptcy protection in the UK and US. Does any of this sound familiar so far?

At around the same time the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) went into liquidation and lost billions of dollars belonging to its depositors, shareholders and employees. In addition, another company, Polly Peck, reported healthy profits one year while declaring bankruptcy the next. Following the raft of governance failures, Sir Adrian Cadbury chaired a committee whose aims were to investigate the British corporate governance system and to suggest improvements to restore investor confidence in the system. The final report was released in December 1992.

While 28 years have elapsed between the report’s publication and the present day, one could swap the names and personalities that drove the original crises with many new ones and, unfortunately, the tale would be almost the same. Poor governance, leading to failure followed by stakeholder and shareholder losses, or if you are ‘too big to fail’ – a government bailout!

The desire to understand why we face similar issues today – poor culture and leadership, and the same lack of trust and confidence in our governance systems – as were present in 1992, has driven my search for answers. I believe the current regime of theories, regulations and codes is simply inadequate in its understanding of how the board and its individual directors influence organisational performance.

Regulators and legislators have envisioned directors in the same manner as traditional economists – as rational decision-makers, operating in an environment devoid of biases, desires, outside influences, etc. The reality is light years beyond this. My work and experiences have taught me that a more nuanced approach is required; one that considers the many behavioural influences that influence and impact individual (director) and collective (board) decision-making processes.

My search has been influenced by many influential thinkers across a range of disciplines. Those who

have been most influential include Richard Thaler, a pioneer in behavioural economics – some may call him the founding father of this discipline. Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner, and his late collaborator, Amos Tversky, have also influenced me greatly, and Jim Collins’ pioneering research methods influenced how I undertook my research.

Through the pioneering work of Richard Thaler, the field of economics now encompasses human behaviour in its thinking, creating the new field of behavioural economics. I believe governance must

also undergo a similar transformation. We must stop this pretence that directors are rational beings, making decisions free of bias, emotions, etc. Instead, we should consider how directors, and therefore

boards, influence organisational performance through their ‘collaborators’, the executive, and how they do this through a lens that might best be described as ‘behavioural governance’.

The Proposition#

The structure of organisational leadership is most often conceived as being two-dimensional. That is, there are two teams, the board and the executive, operating independently of one another, yet residing within the same organisation. My proposition challenges this belief.

What I outline in this paper is a leap forward in our understanding of how boards influence organisational performance through the executive. I outline and provide evidence that organisational leadership is, in fact, three-dimensional. That is, there are not two, but three teams that make-up the trinity of leadership: the board and executive, the traditional two-dimensional theory and the ‘third team’. This team is the most powerful team within the trinity of leadership of an organisation. The third team is formed whenever the board and executive collaborate or meet in formal or informal settings. The use of the term ‘trinity’: ‘tri’ meaning three, and ‘unity’ meaning one, acknowledges that these teams are separate and unique, yet their power, and ultimately the performance of the organisation, comes not from separation, but from

their unity.

Research and experience have identified that organisational performance is intrinsically linked to

the performance of both the board and executive. The performance of one without the other is

only half as good as the combination of the two. The board and executive teams are individually

responsible, yet collectively accountable for organisational performance.

Identifying that organisations have three very distinct teams: board, executive and the third team, was made possible through the research for my doctoral thesis (2012).1 A core finding of this research was that while it is true that a board and executive each have their own distinct roles and responsibilities, it is the third team that ultimately carries the responsibility for the performance, successes or failures experienced by an organisation. Furthermore, within this ‘third team’ environment, a complex web of characteristics, attributes and behaviours either facilitate, hinder or stop the board from influencing the executive, who in turn impact organisational performance, in whatever way that performance may be measured.

For clarity, my definition of the term ‘executive’ refers to the CEO and senior leadership team members, for example, chief financial officer, operations manager, marketing manager, etc., who have regular contact, formal or informal, with the board and/or individual directors.

This paper provides insights into why the third team is so powerful, while also highlighting that it is not a single functional element, for example, independent directors, which determines organisational performance, but rather a complex web of characteristics, attributes and behaviours drawn from individual members and the collective team.

Existing knowledge#

The common understanding on which governance practice and regulation is built, relies on several dominant theories, for example, agency theory, stewardship theory and resource dependency theory.

Alongside these theories, there has been a reliance on board attributes, either single or multiple, for example, composition (diversity), size, CEO/chair duality, independent directors, conformance with compliance, etc. The power to alter organisational performance for the better has been ascribed to these attributes, either collectively or singularly.

Further, trying to reduce a complicated, interactive behavioural environment, which is fuelled by the attributes, characteristics and behaviours that exist both within individuals and between a board and executive, to something that is linear has resulted in legislation as well as codes of conduct developed and prescribed by stock exchanges and other institutions.

Has this myriad of legislation and codes led to an overall improvement in organisational performance? Unfortunately, not. Instead, there have been more systemic failures, for example, those identified in the Australian Royal Commission into Banking, cultural and governance failings of international banks (for example, HSBC, HBOS), corporate failings like BHS, Carillon, Toshiba, Olympus, Fletchers, Mainzeal, and sporting body failings like FIFA, the IOC, International Weightlifting Association, AiBA and many others. In all cases, behavioural and/or cultural failures of the combined board and executive are at the heart of the crisis that has occurred.

Our innate desire to codify or legislate in these complex environments combined with an unwillingness of many boards to open the black box that is governance ignores the complex relationships, behaviours and interactions that occur between the board and the executive. Further, it overlooks a core principle of governance – that it is only through the executive that a board can influence the performance of an organisation. The executives are the gatekeepers between the board and organisational performance.

What follows outlines the research and findings which led to the identification of the ‘third team’, which exists within an eco-system described as ‘behavioural governance’. It starts with a description of how the research sample was chosen and the method of analysis. Following this is a discussion of the results, supported by a brief discussion on the importance of intellectual capital and the part it plays. The characteristics of the third team and how behavioural governance should alter the way we view board performance are then considered, before finally closing with some additional insights and conclusions.

Selecting the sample organisations#

The research adopted a dual-country, New Zealand and Australia, and dual-sector, corporate and not for profit (NFP), approach. New Zealand and Australia were selected because of their long history of co- peration in business and the growing homogenisation of the regulatory, governance standards, practices and processes that is occurring. New Zealand and Australian directors often simultaneously hold posts on the boards of, or work in, organisations in both countries, while the business and NFP environments in the two countries are similar.

Internationally this trend is evident between European Union (EU) countries and to a lesser degree between the EU and the USA. Within the Asia Pacific region, the increasingly close business relationship between NZ and AU ultimately influences the expected standards of governance within each of the countries.

From a governance perspective, the corporate and NFP sectors are often viewed as being homogeneous. This dual-country and dual-sector approach is unique in its scope and scale, providing insights and understanding that may change the way we view the drivers of organisational performance, including that the corporate and NFP sectors are not as homogeneous in their approaches to governance and practice as common wisdom assumes.

Selection of the corporate sample used a two-step process to filter the population of 100 entities in the ASX and NZX top 50 indices combined. Corporates had to:

- not only be listed on the ASX or NZX top 50 indices; but also

- have been listed on one of those indices continuously for more than 10 years (the close-off date was December 2009).

Twenty-one NFPs from across both countries were included in the population. NFPs had to:

- be affiliated with their international federation; and

- have been registered as an incorporated society continuously for more than 10 years (the close-off date was December 2009); and

- have annual revenue exceeding $3 million (AU or NZ dollars).

Organisations were identified as either high-performing or poor-performing, utilising each organisation’s financial data and covering 10 years ending in December 2009. The analysis used a range of financial measures tailored to each sector. To be classified as high-performing, an organisation (corporate or NFP) must have exceeded the 10-year average for each of the financial measures used for their sector. Failure to outperform the average on any one measure resulted in the organisation being classified as poor performing.

Sixty-four organisations reached the initial qualification criteria. Of these, 13 organisations (covering both sector groups and countries) were identified as high-performing organisations. The remaining 52 were classified as poor-performing.

Data was collected via an electronic survey and in-person interviews. Those receiving the survey and being eligible for interview were the chair, directors (minimum of two) and executive staff, the CEO, and a minimum of two other executive members.

Analysis method#

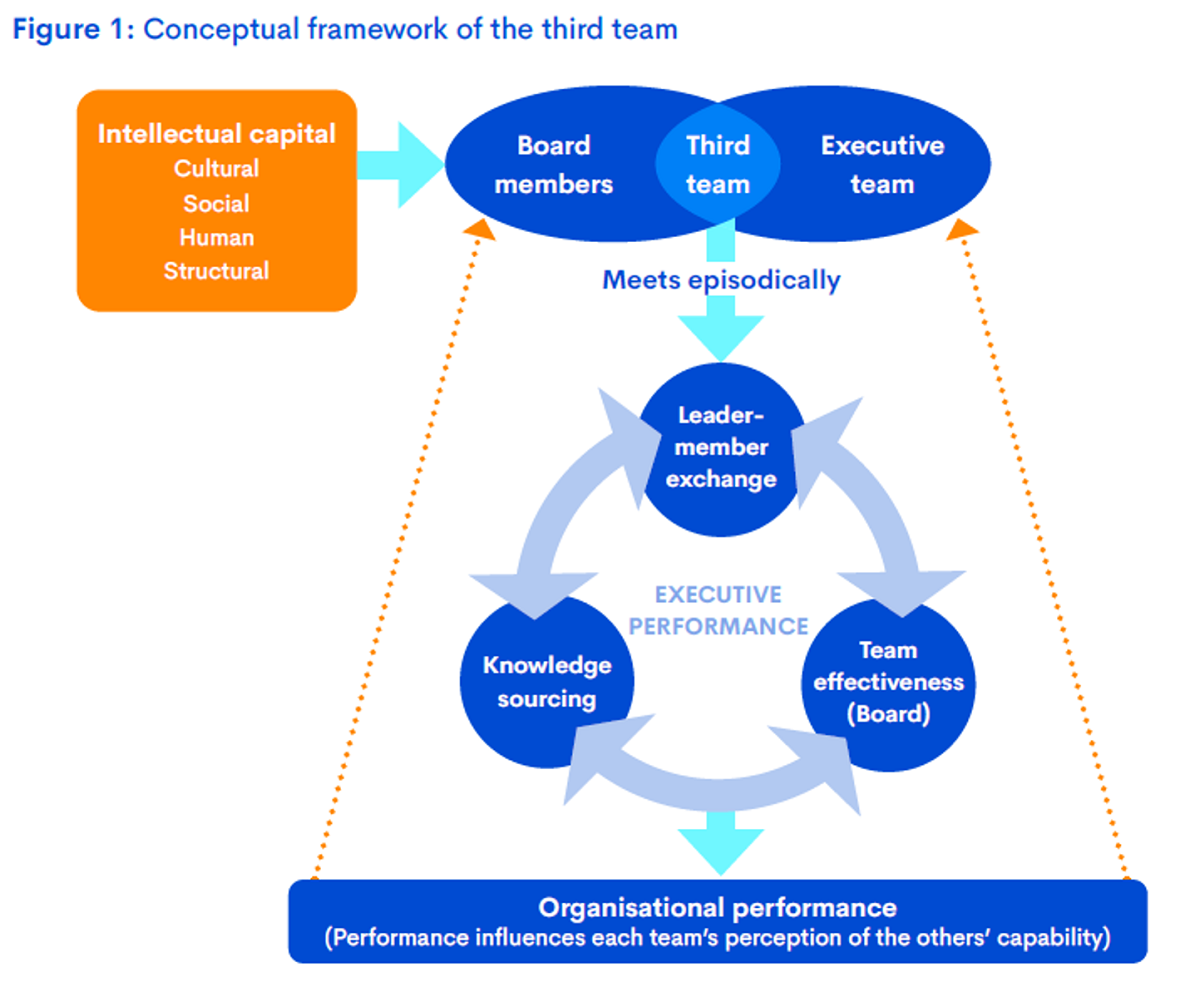

To understand the characteristics, attributes and behavioural elements that may influence/impact the board and executive performance and their organisational performance, four constructs were utilised. These were intellectual capital (social, cultural, structural and human), leader–member exchange, knowledge sourcing and team effectiveness.

From these constructs, 97 measurable elements (board 60 and executive 37) were identified. The extensive and significant amount of data was analysed using fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The fsQCA provided a robust and tested analysis method that permitted the identification of what is described as complex causation.

Complex causation is a condition where an outcome may follow from several different combinations of causal conditions or mix of characteristics (a causal recipe). Each causal recipe is either sufficient or necessary to achieve an outcome. In this case, the outcome was either high or poor organisational performance.

For clarity, it is helpful to provide some definitions:

- A characteristic is both necessary and sufficient if it is the only characteristic that produces an outcome, and it is singular (that is, not a combination of characteristics).

- A characteristic is sufficient but not necessary if it is capable of producing the outcome, but it is not the only characteristic with this capability.

- A characteristic is necessary but not sufficient if it is capable of producing an outcome in combination with other causes and appears in all such combinations.

The key point is not which ‘characteristic’ is strongest, but which of the various combinations of characteristics (causal recipe) are capable of being necessary and/or sufficient in producing the outcome.

The results identified the existence of the ‘third team’ (see Figure 1), which provides the context in which the board influences the executive, who in turn impact organisational performance.

They also confirmed that it is a specific mix of characteristics and attributes contained within the third team and its individuals, which was required for high-performance to be achieved.

Importantly, the results identified that the store of directors’ intellectual capital provides the means of influencing organisational performance and that leader–member exchange, knowledge sourcing and team effectiveness facilitate the interactions between the members of the third team to achieve that performance.

Another significant finding is that ‘synergy’, ‘trust’ and ‘confidence’ are the defining attributes of high-performing third teams. These three attributes are a synthesis of the individual characteristics within the identified causal recipes. All three attributes were present in the third teams of high-performing organisations, whereas one or more of these attributes was missing from the third teams of poor-performing organisations.

The results argued against the widely accepted and unwritten rule that the CEO is the most important point of contact for a board. Instead, the results showed that organisational performance improves when boards take a proactive approach to developing and maintaining good interaction with the wider executive group.

Critically, the results show that corporate and NFP boards are not homogeneous. In fact, the two sectors differ significantly in the ‘third team’ characteristics they require. This suggests that future practice should treat them as unique ecosystems requiring differing approaches if they are to achieve the desired outcome of high-performance.

The third team forms the nexus of interaction between the board and the executive and is therefore the mechanism through which the board influences the executive and, through them, organisational performance (see Figure 1 above). This is consistent with literature that supports the board/

executive collaboration and functioning as a team (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003; Langton & Robbins, 2007;

Payne, Benson, & Finegold, 2009).

The development of a strong third team provides three principal benefits:

- It enables the board to develop a deeper understanding of the assumptions and thinking used by the executive in their decisionmaking, putting it in a better position to guide and oversee executive actions.

- The executive members gain better access to the individual and collective, tacit and explicit knowledge of the directors.

- Organisational performance is enhanced when the board has a wider influence and greater interaction with senior executives other than just the CEO.

Role of Dominant Theories#

Resources in the form of intellectual capital (particularly elements of social capital and human capital) are a key component of the value directors contribute to the third team. These resources are transferred through knowledge sourcing by the executives, who adapt, innovate and/or replicate this knowledge for the benefit of the organisation. This supports the resource dependency theory view of the board.

Agency theory is a dominant framework in corporate governance. Its focus is on how the owners (principal) can minimise agency costs. This means minimising or eliminating managerial opportunism and expropriation of stakeholder and shareholder returns by controlling the executives (management), who are the agents. The focus on control, central to the agency perspective, is not reflected in the causal recipes of the corporate or NFP sectors in either New Zealand or Australian high-performing organisations. In fact, the results show that collaboration and teamwork are critical to performance. These results contrast with agency theory’s reliance on the master–servant (board–CEO) relationship.

Stewardship theory holds that the executives are altruistic; that is, they are interested in seeing the organisation succeed. The theory suggests that this interest extends beyond their tenure. Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson (1997) stated that executives viewed this longer-term organisational success as a personal reflection of their own success or failure. This notion suggests that, from the perspective of both the executives and those outside the company, the executive and the company are one; that is, the success of one directly reflects the success of the other or, conversely, the failure of one is seen as the failure of the other.

Role of Directors#

Directors also share the view that their professional success is linked to the organisation on whose board they serve. This is evident in the high-performing corporate and NFP organisations in both New Zealand and Australia. The characteristics identified within the construct of team effectiveness highlight the directors’ belief that their roles include bolstering the company image in the community, building networks with strategic partners and enhancing government relations.

All these aspects of a director’s role require putting at risk their standing in the community (business and social), which would be unlikely if they did not feel a strong stewardship duty towards the organisation.

The ‘third team’ model is a new conceptualisation of corporate governance and coalitions of teams combined for specific tasks. In particular, the model conceptualises these third teams as comprising an amalgamation of two teams rather than individuals. Importantly, the ‘third team’ model recognises that each team within the newly formed third team keeps its unique team culture and history.

Intellectual capital is often conceived as only encompassing ‘human capital’ whereas it is in fact, an overarching construct that incorporates human capital, social capital (internal and external), structural capital and cultural capital. The intellectual capital of directors determines if they will be worthwhile contributors to the third team.

To influence the executive, the board needs the right balance of characteristics. Crucially, there are only a few similarities between the causal recipes of high-performing organisations and those of poor performing organisations. This lack of similarity emphasises that a board’s intellectual capital is the ‘means’ through which the board influences the ‘end’, that is, organisational performance.

Identifying the presence or absence of characteristics from intellectual capital is critical to understanding if a board can influence organisational performance through the executive. However, the correct mix of intellectual capital characteristics on their own is not enough; they need facilitators that allow the knowledge to be transferred and utilised through adaptation, innovation or replication (AIR).

The individual characteristics in leader–member exchange, knowledge sourcing and team effectiveness act as these facilitators, allowing the intellectual capital of directors to influence the executive in the third team.

Importantly, it has been firmly established that knowledge sourcing is important in facilitating the exchange and transfer of ideas and knowledge between the board and executive. This characteristic of executive behaviour is just as important as leader–member exchange, even though it relies on the latter to facilitate the learning that results from knowledge sourcing. The CEO of a poor-performing organisation discussed his reluctance to engage the board in open discussions on important matters, saying: “if you felt there was a level of cohesion within the group and trust, you’d just go bang, here it is, let’s have the discussion.”

This quote highlights the importance of synergy, trust and confidence within the third team and how directors’ intellectual capital can go unutilised, because these three attributes are missing. When one attribute exists without the other, the flow and interaction identified as essential to high-performing third teams will not occur.

It is critical that boards function effectively as a team, hence the importance of ‘team effectiveness’. Otherwise, the role of leader–member exchange, knowledge sourcing and team effectiveness in influencing the board is weakened. Cohesion and planning ability, specifically as it relates to succession planning for both the board and executive, are critical characteristics of high-performing boards.

It is important to note that this interdependence between the constructs is a significant finding. It takes the combined strengths of each characteristic within the causal recipes of the different constructs to facilitate an organisation achieving high-performance.

Illustrative Findings#

Three distinct types of characteristics/attributes were identified in the causal recipes of third teams:

- those associated with the board and individual directors (team effectiveness and intellectual capital)

- those associated with the third team (knowledge sourcing and leader–member exchange), and

- those that result from the individual and collective characteristics of synergy, trust and confidence.

The combination of these characteristics of the board (collective and individual intellectual capital), which are accessed by the executive through the third team (through knowledge sourcing and leader–member exchange) forms the nexus of influence and power within the organisation. It is the recipe of characteristics mixed within the model of the third team that creates high levels of synergy, trust and confidence. These then allow the board to influence organisational performance through the executive. Identifying the characteristics absent from the high-performing teams and present in poor-performing teams is an important step in understanding how boards influence organisational performance. Examples of these characteristics include:

Human capital: high-performing NFP organisations identified sufficient trust to use director capabilities as a key ingredient, whereas poor-performing organisations did not. This identifies a lack of trust between the board and executive of poor-performing organisations – the executive does not trust the motives of the directors.

Team effectiveness: high-performing corporates boards are effective at shaping and monitoring long-term strategy, whereas boards of poor-performing corporates are defined as being good at managing crises. The need for crisis management by poor-performing boards may result from the lack of involvement in shaping and monitoring strategy.

Cultural capital: Cultural capital focuses on an individual’s implicit and tangible attributes which are associated with the boards sanctioned values, norms and rules, for example, honesty. Unsurprisingly, the findings identified differences between New Zealand and Australia. For example, Australian high-performing corporate boards did not identify that directors must have shared ‘values, norms and beliefs’ whereas for New Zealand corporates the boards identified having shared values as a ‘necessary’ element.

This highlights differences in cultural expectations between New Zealand and Australian high-performing boards and confirms that, even though legislators and regulators may view the two as homogeneous, they are not. The cultural and social capital (internal and external) of boards is an important contributor to board performance. However, it is the characteristics within these constructs that indicate a board’s likelihood of leading a high-performing or poor-performing organisation. For example, poor-performing corporate and NFP organisations in Australia identified board members sharing values, norms and beliefs (cultural capital) as essential in their recipe, whereas high-performing organisations did not.

The importance to boards of shared values, norms and beliefs is often reflected in director recruitment, with candidates being shoulder-tapped from within a director’s inner circle of acquaintances. This ensures the prospective director is a good fit with the current social and cultural mix of the board.

Unfortunately, this limits the gene pool, resulting in ‘inbreeding’ (directors with the same basic ideas, background, contacts, etc.). The social and cultural characteristics of the board and individual directors influence the third team’s ability to use its directors’ human capital (innate and learned abilities, expertise and knowledge).

Limiting executive access to this human capital limits the executive’s ability to access and then adapt, innovate or replicate the knowledge to improve the organisation’s performance.

Selection processes that perpetuate the development of vanilla boards reduce diversity in skill sets and intellectual rigour, and result in the executive not seeing much value in accessing the board’s intellectual capital. This indicates that, before director recruitment begins, the current board’s unique characteristics in relation to its intellectual capital (human, internal social, external social, cultural and structural), leader–

member exchange, knowledge sourcing and team effectiveness need to be identified. This process should include the executive, as they form the key link between the board and organisational performance.

Aligning the skill sets of the board more closely with the organisation’s changing strategic circumstances improves the value a board can add to organisational performance. This is reflected in the executive’s ability to use the directors’ tacit and explicit knowledge. When board recruitment processes are based on the belief that inbreeding provides superior selection outcomes, the eventual decline in board performance and a corresponding decline in organisational performance, is inevitable.

Implications for organisations: Performance Reviews of Boards#

The findings identified three core cultural qualities that all top-performing third teams have in common: synergy, trust and confidence. These qualities are all multi-faceted; that is, they are not attributable to an individual characteristic or attribute. They develop from the collective characteristics and attributes of the individuals within the third team, becoming the third team’s DNA. It is this DNA which determines the levels of synergy, trust and confidence that exist between its members. Equally as important, it facilitates the development of the third team’s cultural norms and values.

Often, the popular methods of review only serve to impress the stakeholder with the idea that a great deal is being done, when, in reality, little is intended to be done. This ensures that it is also harmless to the individual and collective egos of those involved – the directors.

If organisations are genuinely interested in understanding how they influence the executive who then impact organisational performance, it is impossible for them to ignore the importance of reviewing the most influential team in the trinity of leadership, the third team. This new understanding of how a board and executive collaborate as the third team should fundamentally alter how the performance of a board is understood. Conducting a behavioural governance review provides the organisation with a view of the board’s and the executive’s ability to influence performance, which is difficult to replicate.

A behavioural governance review does not exclude the need to review compliance or policy aspects of the board. Measuring the conformance of the board with regulatory, policy or other components of compliance is important. However, the outcomes from these reviews are incapable of reflecting the current capability, nor can they reliably predict the possible future performance of the third team and ultimately the organisation.

Five factors have been identified as influencing a board’s decision to continue using current review methods, which everyone is comfortable with, rather than utilise a behavioural governance review which may highlight areas of dissonance an ambiguity, leading to the need to reflect on the third team make-up.

- the board’s collective preference for simplicity

- the board’s general aversion to any measure that may highlight dissonance and ambiguity

- the board’s deep-rooted belief that they operate in an orderly world, which is somehow disconnected from the executive

- that no one, but them ‘truly understands what they do’, and

- a general lack of understanding of the importance, impact and influence that the collective and individual characteristics and attributes of the third team – their behavioural profile – have on organisational performance.

Using closeted board review processes are, at best, a dereliction of the board’s duty to test the board’s effectiveness and performance. At worst, it is an indicator of the board’s disconnection from the reality of their role and their responsibilities towards the organisation they have been entrusted to govern.

There are five basic questions that a behavioural governance review interrogates, and whose answers provide insights and analysis:

- Do directors enjoy working in a cognitively challenging environment?

- Is the board’s intellectual capital, which comprises human capital, social capital(internal and external), cultural capital and structural capital, consistent with that of the executive and does it match that of the organisation?

- Does the executive make use of the tacit knowledge of the directors through the replication, innovation or adaptation of this knowledge?

- What is the state of the board–executive relationship?

- What is the level of disparity between the board’s and executive’s view of the board’s effectiveness?

It has been shown that where a third team performs poorly across these five primary areas, three outcomes follow:

- There is a lack of synergy, trust and confidence within the third team.

- The third team’s cultural norms and values are ill-defined, resulting in a poor or inappropriate

organisational culture. - Organisational performance declines across a range of metrics, for example, financial, risk,

strategy and succession planning.

Utilising a behavioural governance review allows organisations to develop a profile of their third team. This behavioural governance profile provides the basis on which the third team can review its performance, influence and impact on the performance of the organisation. The profile facilitates this, by enabling the third team to identify its weaknesses and/or strengths and put in place remedial actions. The behavioural governance profile also provides the opportunity to develop and enhance the skills and functionality of the third team, empowering the third team to drive their organisation’s performance in a collaborative and mutually accountable way. And surely that is what reviews should achieve? The mplications for reviews and assessments of board effectiveness are significant, given that the boards of poor-performing organisations consistently over-estimated their effectiveness when compared with the executives’ assessment.

In contrast, the boards and executives in high-performing organisations were consistent in their assessment of the board’s effectiveness. This disparity between the assessments of a board’s effectiveness by the boards and executives in poor-performing organisations compared with the agreement displayed by the boards and executives in high-performing organisations is significant. It highlights that including the executives’ view of board effectiveness is critical to understanding the third team’s overall performance and its influence on organisational performance.

Conclusion#

The ‘third team’ model challenges a range of closely held beliefs within governance circles. These beliefs result in the failure of executives to use the board’s intellectual capital as a strategic resource for the benefit of the organisation.

Contrary to popular belief, defining the combined board and executive as the third team does not imply the destruction of organisational hierarchy. In fact, the third team facilitates the continuing existence of hierarchies and structures; it defineshow the boundary between board and management is bridged, enabling the board’s intellectual capital to improve organisational performance. And surely that’s what they’re there for?

As long as hierarchy and structure add value to performance, there will be a need for the relational space defined as the third team to span these boundaries. A board’s ability to influence the performance of

the organisation it governs ultimately depends not on one characteristic, but on a complex mix of multiple characteristics, attributes and behaviours.

Importantly, this paper briefly outlines that it is specific characteristics, attributes and behaviours that facilitate a board’s ability to influence organisational performance. This has led to the understanding that it is the behavioural governance of the board and executive, combined as the third team, who influence organisational performance.

Dr. Denis Mowbray