NZSA Disclaimer

Property investment has a long and storied history in New Zealand. It’s a sector that has thrived in the low-interest rate environment enjoyed by New Zealanders over the last decade and supported by our clear requirement for additional housing and higher-quality commercial property assets.

The last few years, however, have seen some cracks emerge, particularly amongst ‘unlisted’ property funds and syndicates. Many will recall the issues associated with Maat Group, and the ill-fated involvement of retail investors in the development and construction of the Nido warehouse in West Auckland. More recently, investors have become more aware of the perils of investing in an ‘unlisted’ property syndicate as they’re unable to sell their investment. And so far in 2024, we’ve seen the apparently successful conversion of limited partnership syndicates associated with Du Val into shares in a newly-constituted Du Val Group – a company that, on current appearances, does little to promote the cause of investor transparency and independent governance, and is likely to carry significant ongoing risk for minority investors.

In future articles, we’ll go into a bit more detail around each of these specific investments – and the key lessons for investors.

For now, though, this article (the first in a series) sets some context. Why do New Zealander’s have such a strong connection to property investment? And what options are available to support property investment?

Government and institutions

The sector has been unconsciously favoured by various flavours of government for over 50 years, with a variety of regulations, incentives and tax benefits that have made ever-increasing levels of leverage against property a rational decision for property investors. This unconscious bias has fed its way into the financial institutions that support economic activity in New Zealand. For example, have you ever tried to borrow money from a bank secured by your investment portfolio, to add to said investment portfolio? Good luck with that. Invariably, the cheapest and easiest method to borrow money for investment purposes is to secure any loan against a property, regardless of what the loan is actually going to be used for.

In that context, it’s no coincidence “safe as houses” has become an expression embedded in our everyday language and culture.

I might argue that borrowing money to invest in a single asset, in a single location, with uncertain future cashflows, should be regarded as inherently riskier than borrowing money to invest in a basket of shares and funds comprising globally-diversified investments in a range of businesses and sectors, that return a relatively stable set of cashflows each year.

But that’s not how a typical New Zealand bank sees it.

Perhaps this has less to do with risk than convenience for our major institutions. The afore-mentioned unconscious bias for over half a century means that lenders have developed a huge capability in the systems and processes needed to hold real estate as security. There is very little capability amongst our major banks to hold security against shares or funds (through custodial arrangements or other means).

In the last few years, we’ve seen some clunky attempts by government to negatively discriminate against property investment – through the application of bright-line tenure requirements (a form of capital gains tax) and a decision to not allow tax-deductibility of interest costs used to support property investments, currently being unwound by the current government.

For investors in global share portfolios, there is also some specific negative tax discrimination – in particular, the application of a FIF (foreign investment fund regime) that kicks in at a relatively low level of $50,000 of overseas investments and the non-allowance of franking credits received from Australian listed issuers.

I am no supporter of non-deductibility of interest costs for any specific sector – this is a fundamental challenge to the notion of legitimate expenses and associated income. I also question how that could be applied in the context of a “mixed” portfolio comprising residential property and share investments, where the purpose of the loan is to leverage against both.

But for most capital markets investors, it’s a moot point – in general, they can’t get a loan secured by their investments anyway.

Please know that I am not ‘anti’ property investment. It is a valuable component of a diversified investment portfolio, and there are a variety of methods for individual investors to invest in the sector (including directly).

All any investor wants is a level playing field upon which to base their decisions. Tax or institutional policies, in and of themselves, should never be a reason upon which to base an investment decision.

Property investment options

There are more ways to invest in New Zealand real estate than simply buying a house. As always, for advice, talk to a financial advisor who will be able to relate any potential investment to your own circumstances.

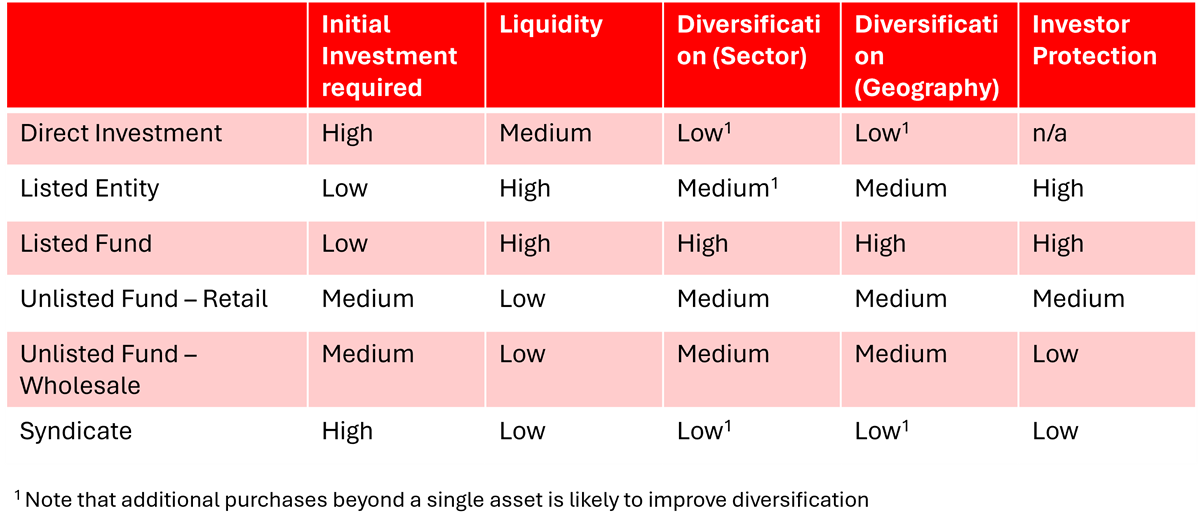

The table below shows a summary of the options available for potential investors – there’s a bit more detail provided below for each option.

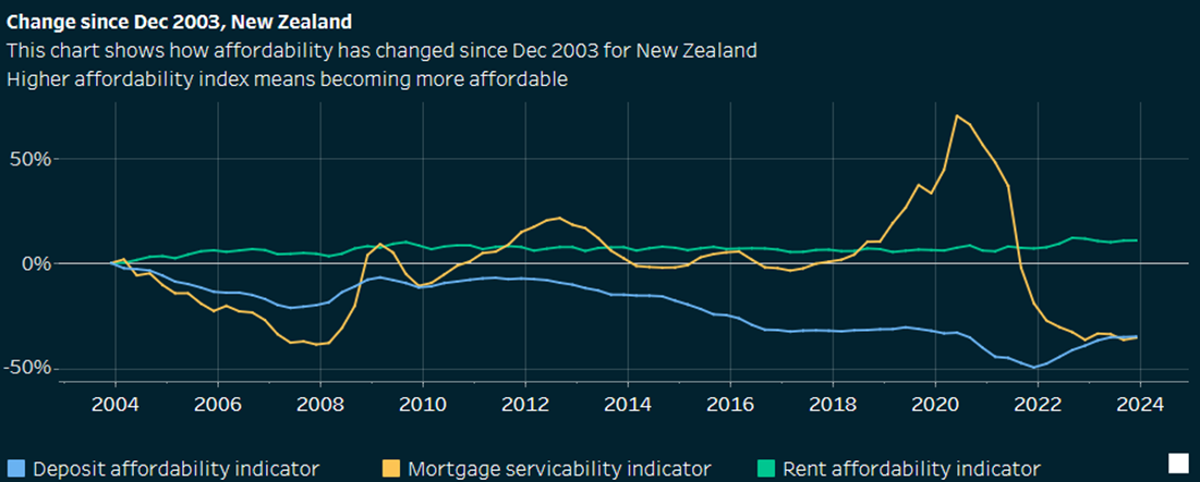

Direct Investment: This form of direct property investment is the one most known to New Zealanders, often achieved by buying their first home, building equity in that asset and then leveraging that additional equity further to purchase an investment property. However, the current relationship of incomes to house pricing makes that approach more difficult for many younger New Zealanders. The chart below reflects a common concern for many – it’s hard to save for a deposit fast enough. Concerningly for existing owners, the change in interest rates over the last few years has had a significant impact on mortgage servicability.

Furthermore, an investor with a single asset is much more exposed to volatility risk both through a lack of diversification (geographic and sector) and the uncertain significant cashflow associated with the sale of a single asset at a point in future. Both risks reduce as more investment properties are added to a portfolio.

If you cannot afford the deposit required to directly purchase a property investment – or even if you can, but want to give yourself more diversified exposure, what other options are out there?

Listed Entities: There are a number of listed entities on the NZX that invest specifically in different sectors of New Zealand property, as highlighted in the table below. Note the retirement sector (not shown in the table) may also be considered as a ‘proxy’ for residential property sector investment – while their business models are targeted towards the retirement sector, this includes extensive investment in what could be considered residential property.

Listed entities offer good diversification of properties within their respective sectors, investor transparency and strong governance. However, each is clearly focused on a specific sector within New Zealand – so an investor may favour investment in multiple listed companies to achieve stronger levels of diversification.

In recent years, there have been two key trends underpinning the development of listed property: firstly, a transition to internal management rather than having their developments and/or investments managed by an external property manager (‘internalisation’) and secondly, a transition to a ‘corporate’ structure rather than a trust structure. Ultimately, this trend reflects a long-term cost/benefit trade-off for operating these types of companies – and also offers shareholders a more direct relationship with their assets.

More recently, a focus has once again emerged on internal separation of ‘property management’ and ‘property investment’, as operators look to structure their affairs to offer tax benefits to their shareholders. For this reason, both Precinct Property and Stride Property operate as “stapled” securities, which means shareholders own shares in two separate-but-related companies under each ‘ticker’.

| Ticker | Name | Sector | Structure | Management | Predecessors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARG | Argosy Property | Office / Commercial | Company (since 2012) | Internal (since 2011) | ING Property Trust Urbus Property Walthus Investments |

| GMT | Goodman Property Trust | Industrial | Trust | Internal (since 2024) | |

| IPL | Investore Property | Retail | Company | External Mgr (Stride) | Stride Property |

| KPG | Kiwi Property Group | Retail Mixed Use | Company (since 2014) | Internal (since 2013) | — |

| NZL | NZ Rural Land Company | Farming | Company | External (NZRLM) | — |

| PCT | Precinct Property | Office / Commercial Mixed Use | Company (since 2010) | Internal (since 2022) | AMP NZ Office Trust |

| PRI (Catalist Exchange) | Prime Campus | Student Residential | Company | External | |

| PFI | Property for Industry | Industrial | Company | Internal (since 2017) | — |

| SPG | Stride Property Group | Property Mgmt Office Mixed Use | Company | Internal | DNZ Property Fund |

| VHP | Vital Healthcare Property Trust | Health | Trust | External Mgr (Northwest) | — |

Interest rates form a significant factor for the sector as a whole (regardless of investment type). In general, the higher the interest rate, the lower a property’s value will be – as there is less available cashflow available for distribution back to the investor after paying interests costs and because there are less risky opportunities available for investment elsewhere (eg, bank deposits).

That is reflected in the sector as a whole right now, with share prices negatively correlated to increased interest rates.

Listed Funds: The listed companies detailed above offer specific exposure to different types of property investments within New Zealand. But there are also three NZX-listed exchange-traded funds (ETF’s) available that offer broader exposure.

- NZ Property ETF (NZX: NPF) offers investment in all of the NZX-listed investments described above (excluding Prime Campus and NZ Rural Land Company).

- The Australian Property ETF (NZX: ASP) allows exposure to ASX-listed property investments. Many ASX-listed property companies operate with investments outside Australia, giving a broader global exposure.

- The Global Property ETF (NZX: GPR) gives exposure to a global basket of property companies, excluding Australia.

Many investors may choose to ‘mix and match’ between these three funds and specific investments as a way to diversify their holding and reduce the volatility of returns.

Unlisted Funds: From this point on, however, things start to get a bit murkier. There are a number of unlisted funds available for investors in New Zealand, differentiated between retail and wholesale investments. A wholesale investor is someone who is able to make an investment in a particular product comprising no less than $750,000 or self-certifies themselves as ‘eligible’ by way of their investment capability. This requires sign-off from a suitably qualified professional (such as accountant or financial advisor) that they have the skills required to operate as a wholesale investor.

NZSA has attended a meeting in the recent past where someone has declared to the attendees that being a wholesale investor is “easy”, and he would happily sign off anyone in the room if they wanted to participate in the wholesale investment opportunity that was on offer. That’s an indication that some in our financial community to not take their responsibilities seriously when it comes to the significantly elevated risks involved with most wholesale investments. In some cases, the issuer raising investment funds operates a service to certify potential investors as wholesale investors under this test…surely a case of foxes guarding the henhouse if ever there was.

The reality is that wholesale investors have far less protection under law than those offered to retail investors, with investments being inherently riskier as a result.

NZSA believes there is plenty more effort required from legislation and enforcement agencies (including the FMA) to tighten up prevailing attitudes relating to wholesale investors within some financial practitioners.

There are a number of unlisted property funds targeting both retail and wholesale investors. For example, Tauranga-based PMG Funds offer five funds for retail investors – although we note that product disclosure statements don’t appear to be readily available on their website. Whether wholesale or retail, your initial investment is ultimately ‘locked’ until the time that the fund wound up. Units are often ‘non-redeemable’, and without a viable secondary market. This limits an investors’ ability to sell their units to those few other purchasers who have expressed interest to the fund manager.

Examples of wholesale funds are those offered by Christchurch-based Williams Corporation and Auckland-based Du Val Group. It is noteworthy that in October 2022, the FMA issued a formal warning to Williams Corporation for relying on a wholesale exemption when it should not have done so. Du Val hasn’t escaped attention from the regulator either: it was directed by the FMA in late 2021 to “remove advertising materials likely to mislead or deceive investors” in relation its Mortgage Fund Limited Partnership. In addition, while the fund was available only to wholesale investors, the FMA noted that “Du Val appeared to be using social media and other online channels to target less experienced investors.” Du Val unsuccessfully appealed the direction order in March 2022. Funds associated with Du Val again received formal warnings in October 2022 (relying on a wholesale investor exemption) and March 2023 for “engaging in “engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that is likely to mislead or deceive investors.” This latter warning related to Du Val’s proposal to cease distributions and convert unitholders interest into a new company; the FMA contended that the actual reason for halting distributions was that the fund had run out of cash.

Most recently, Du Val has hit the headlines again as it converts unitholders in most of its funds to shareholders in a new entity, “Du Val Group“. Unfortunately for these shareholders, the new company falls far short of the independent governance standards expected by NZSA, especially coupled with the 74.6% ownership interest retained by Du Val founders, Kenyon and Charlotte Clarke. As recent events at PGG Wrightson and Burger Fuel have demonstrated, there is significant risk for minority shareholders on the NZX with the protections afforded by the listing rules, let alone for minority shareholders in an unlisted entity. Our Companies Act is woeful at managing investor protections in this situation.

In the interests of balance, I should highlight that there are other retail and wholesale investment opportunities for investors that have not attracted the attention of the FMA. But regardless, underlying risks relating to lack of liquidity and independent oversight remain. For most retail investors, the listed companies provide plenty of opportunity to invest in the sector and generate a long-term investment return.

Property syndicates: These entities, structured as either companies or limited partnerships, have been a common feature of New Zealand’s property market for many years. Stride Property, now a listed issuer, began as an investor and manager of syndicate properties, before morphing into the DNZ Property Fund and then Stride Property Group.

A syndicate is a group of investors brought together purchase an interest in a single property, either by way of a limited partnership or a company. Commonly, this is an ownership interest only – property management may be undertaken by a separate entity, with the costs deducted from the returns available to investors.

Most syndicates are only available for wholesale investors. The FMA offers a simple summary of syndicate structures and the risks/benefits for investors at this link.

Whether wholesale or retail investments, there is some risk associated with syndicates for individual investors, mainly associated with liquidity, governance and underlying diversification. Syndicate structures usually offer an interest in a single building (rather than a portfolio), with the same liquidity risk faced by investors as described above for unlisted funds. Governance elements may also be of concern to investors, featuring a lack of independent oversight and/or related party directors.

At the top of this article, I recalled the development of the Nido warehouse in West Auckland as an example of the risks for investors inherent in a single-asset property syndicate. Next week, we’ll delve a bit further into this tale.

In the meantime, perhaps temper those rose-tinted glasses slightly when looking at how you choose to invest in NZ property.

Oliver Mander

Oliver is the CEO of NZ Shareholders’ Association. This is the first of a series of articles looking at property investment and some specific examples of issues facing the sector.

3 Responses

Considering the complexities and risks highlighted in the article, what steps can individual investors take to ensure they are making informed decisions when exploring property investment opportunities in New Zealand? Thank you!

That is exactly what we are trying to unpick for investors in the commentary above. It’s important to examine your own level of risk appetite as an investor – and recognise that the different options outlined above come with different levels of risk and investor protections. A listed property company investment is a way for most individual investors to gain a diversified portfolio with some degree of protection. But the level of return is (in theory at least) likely to be less than a leveraged, single-asset direct property investment which is inherently riskier.

Thanks Oliver

An interresting and helpful analysis and overview of property investing